September 5, 2023

Mikaely Evans was one of seven college students from across the country who supported tree science at The Morton Arboretum this summer. For 10 weeks, they participated in research experiences for undergraduates through the National Science Foundation. The Tree Science in the Anthropocene program, which includes a stipend as well as housing and travel, gives students the opportunity to conduct an independent research project under the guidance of a PhD-level mentor. They gain experience on all aspects of the research, from reading the primary literature, experimental design, and collecting and analyzing data, to presenting the results at a final symposium. Mikaely shares her experience working in the Arboretum’s Tree Conservation Biology Lab.

The Morton Arboretum is my home away from home. I grew up hiking the trails with my family, biking with my friends, and taking in the beauty of nature.

Many years ago, I was on a walk with my mom and we saw a researcher at the Arboretum using a ladder to pick some leaves off of a tree. We stopped and had a conversation with him about his research. I don’t remember the details, but I do remember how I wanted that to be me one day. I remember the desire I had to grow up and answer the call of nature by learning about how the Earth’s creations are so deeply intertwined, and to continue this passion at The Morton Arboretum. Years later, I am a college junior studying biology and data science, and this summer I worked my absolute dream job. I am the one picking the leaves off the trees!

The Arboretum is a sanctuary for an expansive collection of rare trees from all over the world. This summer, I studied the reproductive patterns of white oak tree species as part of the Hybrid Acorns Project in which the Arboretum is working with the United States Botanic Garden. Oak trees also have the uncommon ability to reproduce across species lines with other types of oaks, which makes them particularly fascinating to study. Traditionally, species are defined as being “reproductively isolated,” which means that individuals of a species are not able to mate and produce viable offspring with individuals of a different species. In the case of oak trees, these species lines are blurred. This pattern of mating across species lines is called hybridization.

Hybridization can pose a problem to conservation at The Morton Arboretum and similar gardens across the world, because it may compromise the integrity of their collections of rare trees that need to be protected. Our project aims to help botanic gardens be better homes for rare oaks by finding ways to maintain genetic diversity in their collections. For example, if we wanted to use acorns from a rare species of white oak tree for restoration purposes, we would want to be sure they had white oak genes. We would not want those acorns to be influenced by hybridization, because the acorns wouldn’t accurately represent the population as it was in the wild or the natural genetic diversity of the species.

My day-to-day work over the summer consisted largely of collecting leaf samples from potential parental oak trees on the Arboretum grounds for DNA analysis to see how much they vary genetically. My favorite part was cutting up the leaves, because they smell amazing and it’s a very peaceful process. As we analyzed the samples, some of the major questions we are asking are: “Is reproduction affected by distance or similarity of species?” and “Is one tree species hybridizing more frequently than the rest?” The results of our study will be able to provide guidance for saving endangered white oak species.

While my family teases me for being a tree-hugger, I know my work is important to the future of white oak trees locally and globally. Being involved in this project has opened my eyes to focus on larger-scale conservation efforts shared across the world. I feel such a strong passion to continue working with conservation biologists, because there is a lot of work to be done to ensure the safety and health of our Earth.

Here is a photo of my team using a pole pruner to clip leaves from a very tall, very old white oak tree. We spent about two weeks collecting our samples, sometimes walking through poison ivy and tick-infested brush, but it was very cool to experience the field work of a geneticist.

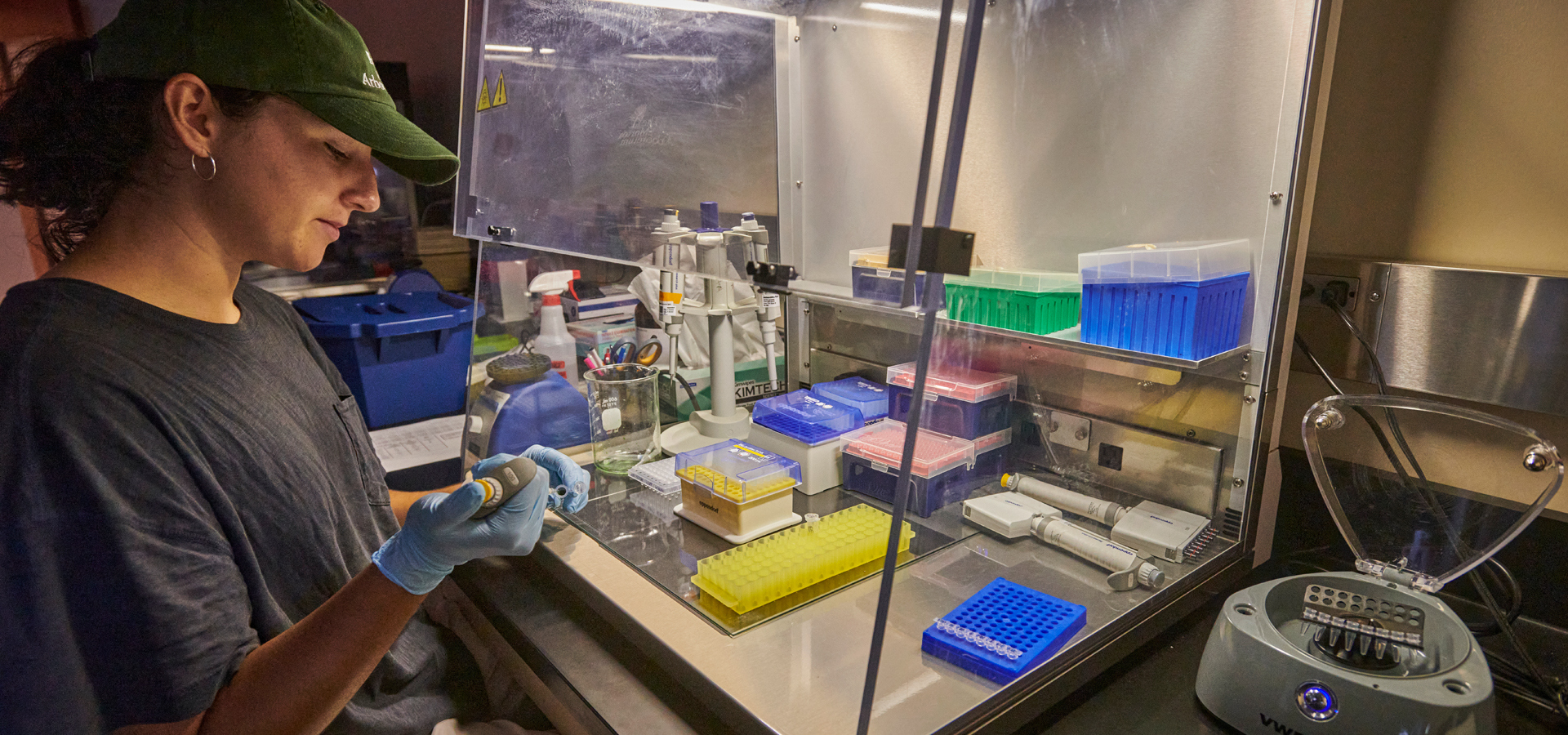

I was performing a DNA extraction. It involves combining leaf samples with very small volumes of soapy chemicals that break up the non-DNA components, and then using a spinning machine to filter out everything except the DNA. This was a very tedious process, which took me four and a half hours the first time I did it. However, I am proud to say that I had successful extractions every time.