Old Trees Remind Us of Our History

Somewhere in your memory, there’s a big old tree. You climbed it, or you walked to school beneath its branches, or your toddler played in its shade, or you knew, when it came into view, that you were almost at the ballpark.

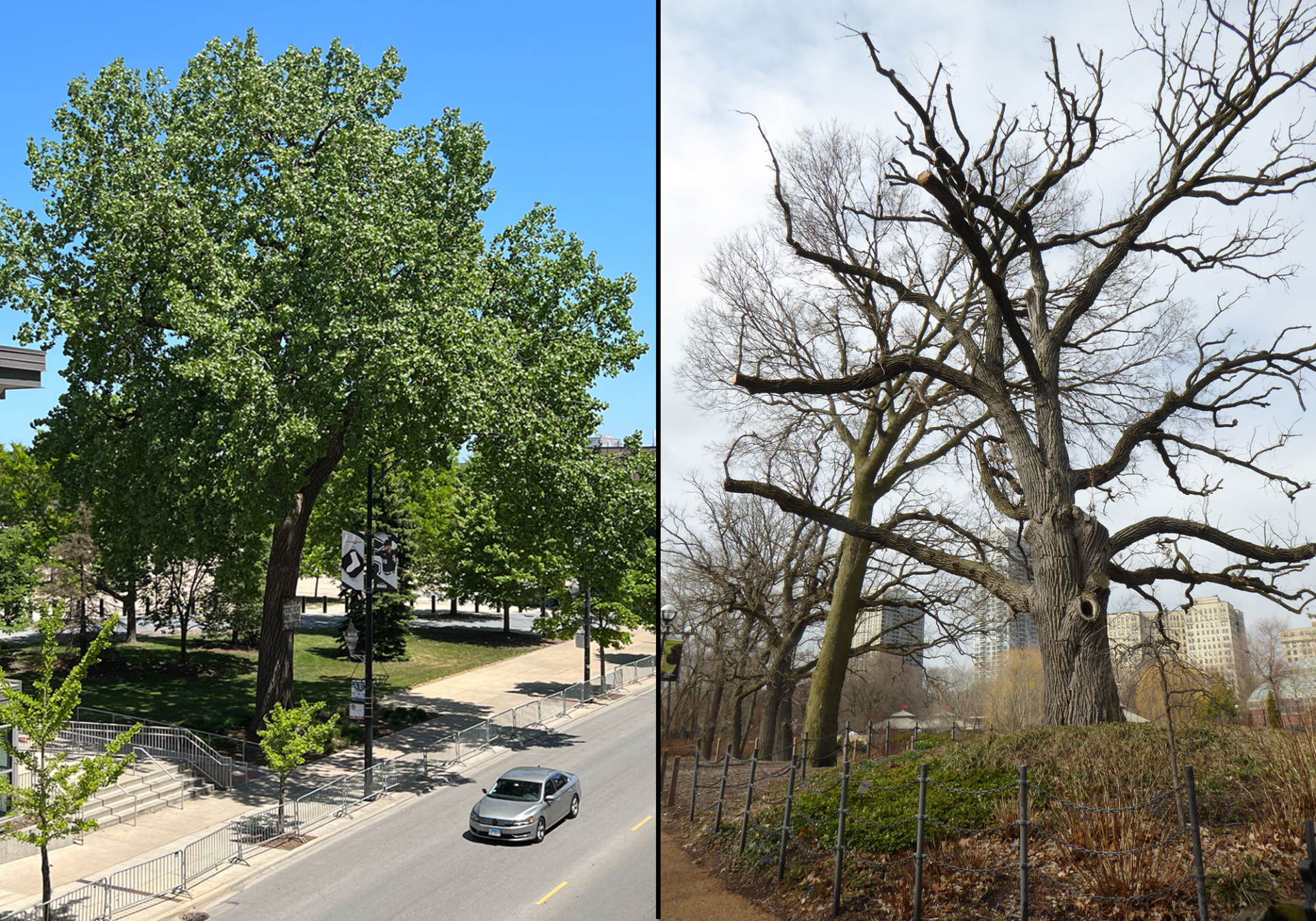

Just outside Rate Field, the current home of the Chicago White Sox, there stands a tall cottonwood that has been welcoming fans for more than a century, since the now-demolished Comiskey Park was under construction (at left, above). From vintage photographs, Kris Bachtell, who recently retired as vice president for collections and horticulture at The Morton Arboretum, determined that the tree was planted as a sapling in 1910.

The tree grew through the first All-Star Game in 1933 and four Sox World Series. It was there when Bachtell went to the ballpark as a child.

For a fast-growing cottonwood, 115 years is a ripe age, and this veteran player may not last too many more decades. But it will have a future. About two dozen cuttings from its branches are growing in pots in a greenhouse at the Arboretum. When these little cottonwoods are big enough, they will find new places to grow.

Bachtell loves big old trees and he knows many of them. In his 43 years at the Arboretum, he cared for grand old oaks that were already full-grown when the Arboretum was founded in 1922, as well as thousands of trees from around the world that have been planted since.

He has also kept a lookout for surviving heritage trees, the ones that have managed to keep growing for decades, no matter how much people changed the world around them: a stately old American elm that is now squeezed into a narrow parkway in Naperville; a huge slippery elm, another native species, in a Lemont churchyard; an Asian elm at the Arboretum that gave rise to the successful Accolade™ elm cultivar that has been planted in cities around the world.

Many big trees are lost, with all their history. They may be cut down to make way for buildings and roads, or die from infestations such as emerald ash borer and Dutch elm disease. Trees along streets suffer from winter after winter of road salt and other de-icing chemicals. The changing climate, with its storms and hot spells, is an increasing challenge for many trees. Droughts take a toll.

But some trees die simply because their time has come. “Trees have a lifespan,” Bachtell said. “They don’t live forever.”

One heartbreaker was a huge, widely beloved bur oak at the Lincoln Park Zoo that had to be felled in 2023 because it was mostly dead (at right, top picture). It was one of several oak trees that were already growing when the zoo was built in 1868. After the tree was cut down, Arboretum researchers dated it to 1857 based on the annual growth rings in its wood.

Though the tree is gone, its genes are not, because the zoo’s horticulturists took cuttings from its few remaining live branches. Expert growers at the Arboretum grafted the cuttings onto new oak rootstocks and potted them up to begin growing at the Arboretum and the zoo. Within the next few years a young sapling—with the genetic and historical legacy of that grand old oak—will be taking root among the animals.

The Arboretum has also grown saplings from other historic trees, such as a 250-year-old oak that was cut down in 2016 in Naperville, and some of the oldest oaks in Oak Park.

Bachtell has enjoyed propagating these trees for their human history and their meaning for people, not because they are special examples of their species. “An old tree is not necessarily genetically superior because it’s lived a long time,” he said. “It may just have been lucky.”

A tree’s history can outlive it in another way: Scientists can learn from its growth rings. The rings not only tell the age of the tree, but can provide important data about the climate it has lived through during its many decades of life. A fat ring records a year with abundant rainfall that helped the tree grow fast; a skinny ring indicates a dry year. Such dendrological data is important to climate research.

Slabs from the Lincoln Park Zoo oak were given to the Illinois State Archeological Survey and added to the Arboretum’s Wood Archive, a cache of sections saved from trees that have had to be felled from its tree collections and natural areas.

As useful as it is to save genes and data from heritage trees, Bachtell would prefer to save the trees themselves as long as possible. Large, mature trees are the ones that provide the most benefits for people, such as shade, cooling, capturing rainwater, clearing air pollution, and improving mental health. They produce the most economic benefits, such as higher property values, and they support the most wildlife.

“If you have a big old tree, take care of it,” Bachtell said. Have it inspected periodically by a trained tree professional to check for problems, he said, because “old trees accumulate troubles, and all living organisms have vulnerabilities.”

Allow it space, giving its roots room to spread out. Cover the roots with a layer of mulch. Protect the tree from construction damage. Water it during dry times. “Show it respect and celebrate it,” Bachtell said. “That tree has lived through a lot.”