The Morton Arboretum’s Chicago Region Trees Initiative has identified places in the Chicago region where there are fewer trees, leading to greater challenges than those faced by communities with ample mature trees.

A lack of trees is related to increased flooding, poor air quality, high temperatures from the sun’s heat stored in masonry and paving, and increased health risks. CRTI prioritizes the most vulnerable communities for tree planting, stewardship, grant making, and many other efforts. It provides an interactive map of tree canopy in Chicago-region communities to identify where needs are the greatest so we can work collectively to reduce this disparity.

In many cases, the lack of trees and the problems their absence brings to communities are the lasting results of longstanding racial discrimination. Communities with reduced tree cover are often those affected by redlining, the past practice of denying home loans in certain areas based on race. The historic lack of investment in redlined areas included a lack of tree planting and maintenance. Please take a moment to read a short explanation of this practice and its effect on the region’s canopy cover.

It is critical to address the effects of systemic racism and discrimination on the region’s tree canopy because access to green space has measurable health benefits that have been identified by researchers. The presence of trees has been shown to speed hospital recovery and reduce stress levels and is correlated with lower rates of death from pulmonary and cardiovascular disease. Mature trees also improve property values, shade and cool streets and homes, help mitigate flooding, and reduce air pollution. Many neighborhoods do not have equal access to trees and green space, so these green benefits are not equitably available.

You can work with The Morton Arboretum through CRTI to help distribute the many benefits of trees equitably across the entire Chicago region and throughout Illinois. Get involved with CRTI to improve environmental justice and equity, reduce disparities, and make the benefits of trees available to all.

Legacy Impacts of Redlining on Canopy Cover

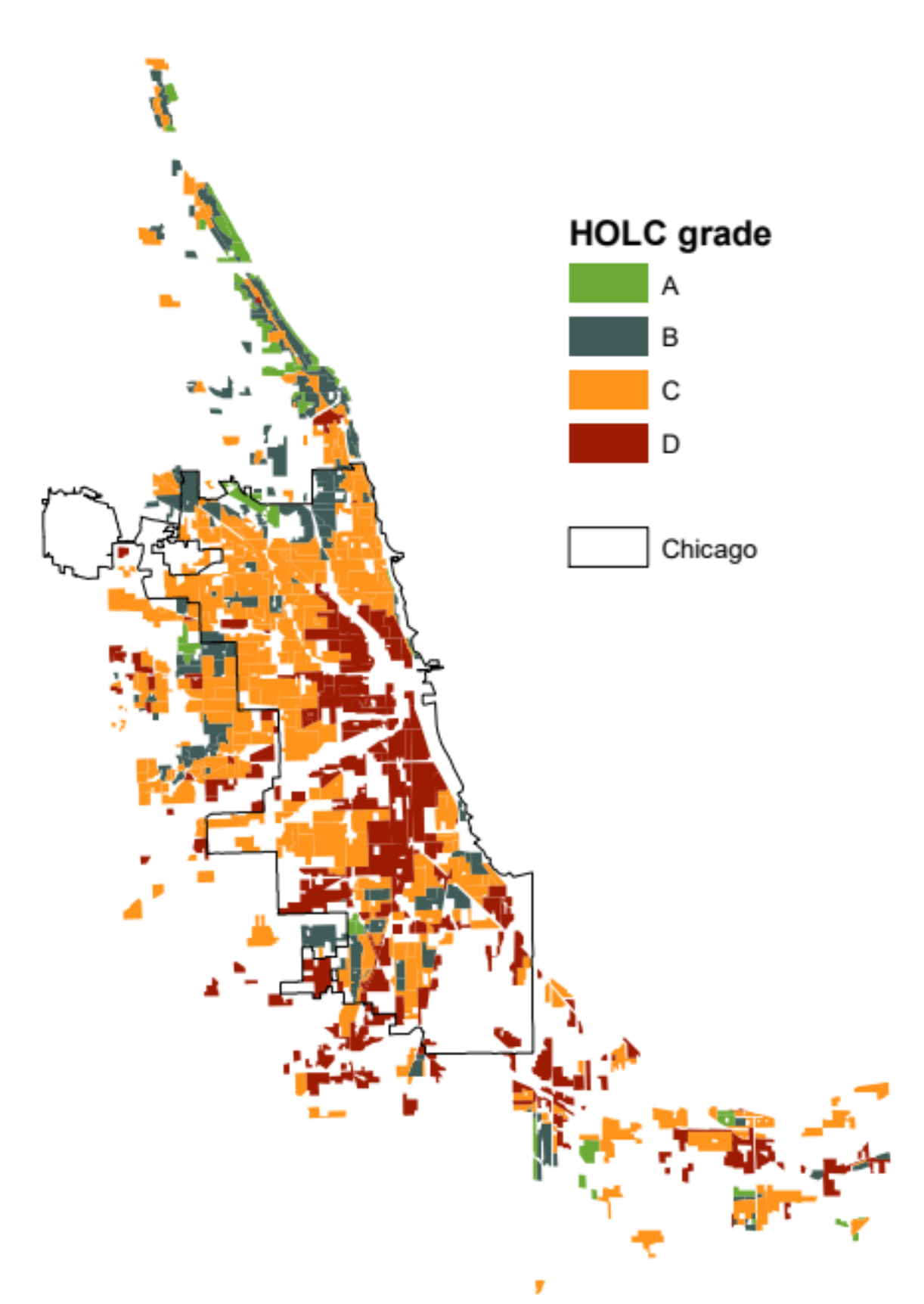

In 1934, the federal government set up the National Housing Act. The program provided low-cost loans that encouraged home ownership during the great depression. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) was tasked with rating the risk associated with the loans. HOLC divided neighborhoods into four categories, and race was explicitly used for the rankings.

A: Safest, predominately white and US-born residents with the newest structures

B: Still desirable, slightly older buildings, predominately white residents

C: Declining, some foreign-born people, older buildings

D: Hazardous, mostly black and foreign-born people, oldest housing stock

The D-rated neighborhoods were colored red on these maps, giving rise to the term “redlining.” People in those neighborhoods did not receive loans, which led to discrimination in other kinds of investment. Though the practice of redlining was officially ended in the 1960s by the Fair Housing Act, the impacts can still be seen on these communities today.

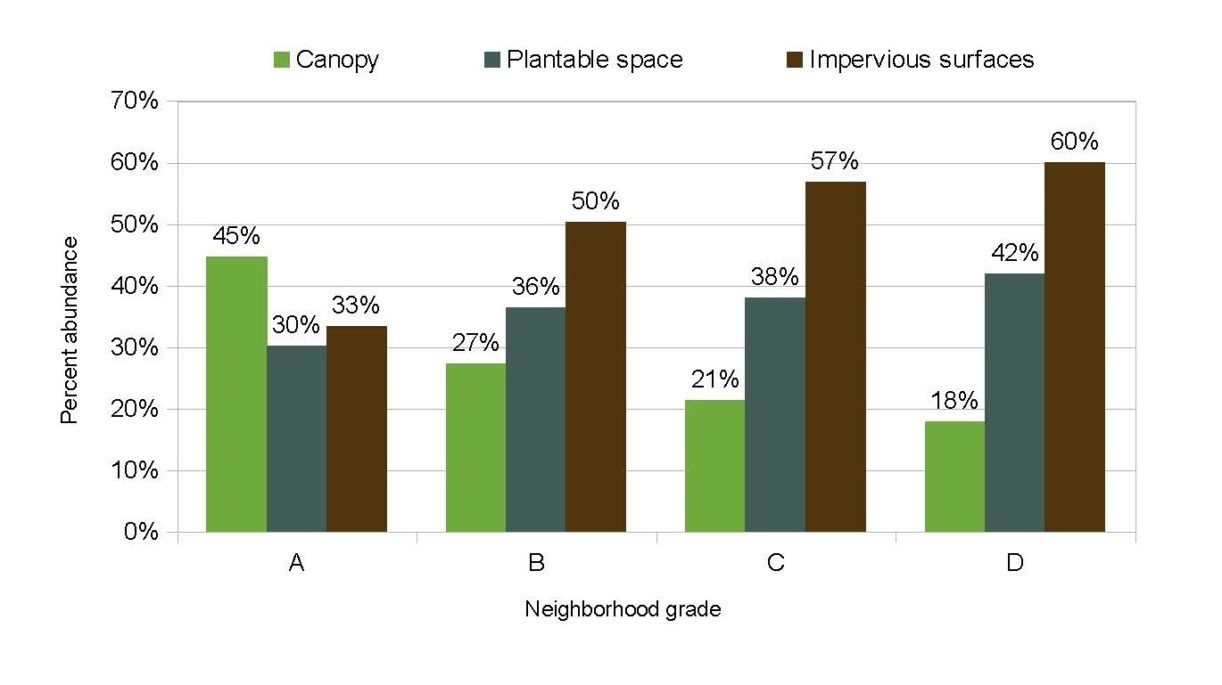

Nationwide, formerly redlined neighborhoods have lower home values, higher surface temperatures, and half as many trees as affluent neighborhoods. In Chicago, there were few grade-A neighborhoods, and they look different from the D-ranked areas. On average, A-ranked neighborhoods have 27% more tree canopy and far less paved impervious surfaces. Formerly redlined neighborhoods generally have the greatest need for planting trees and expanding the canopy.

For more information on the subject, check out this NPR article and video on redlining. It contains links to current research and further delineates redlining’s current impacts on cities.

Figure 1: HOLC grading of Chicago neighborhoods. Most of the city was considered to be hazardous or declining, with some higher-ranked neighborhoods along the north branch of the Chicago River and on the South Side near Beverly. Many suburbs along Lake Michigan north of the city were also ranked A.

Figure 2: Lower-ranked neighborhoods have less canopy and more paved impervious surfaces, but more available space for tree planting to expand the canopy.