Professional Management Resources

Fredric Miller, PhD, senior scientist, entomology, The Morton Arboretum

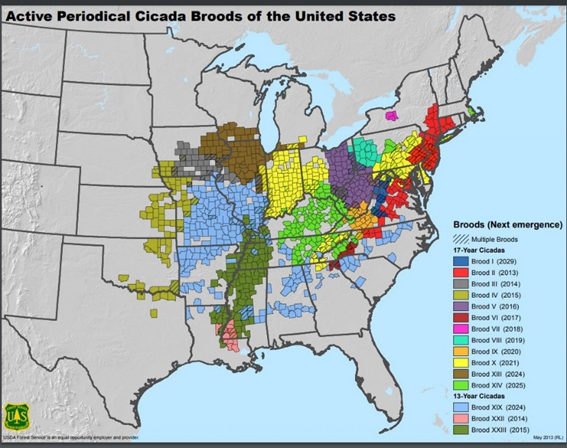

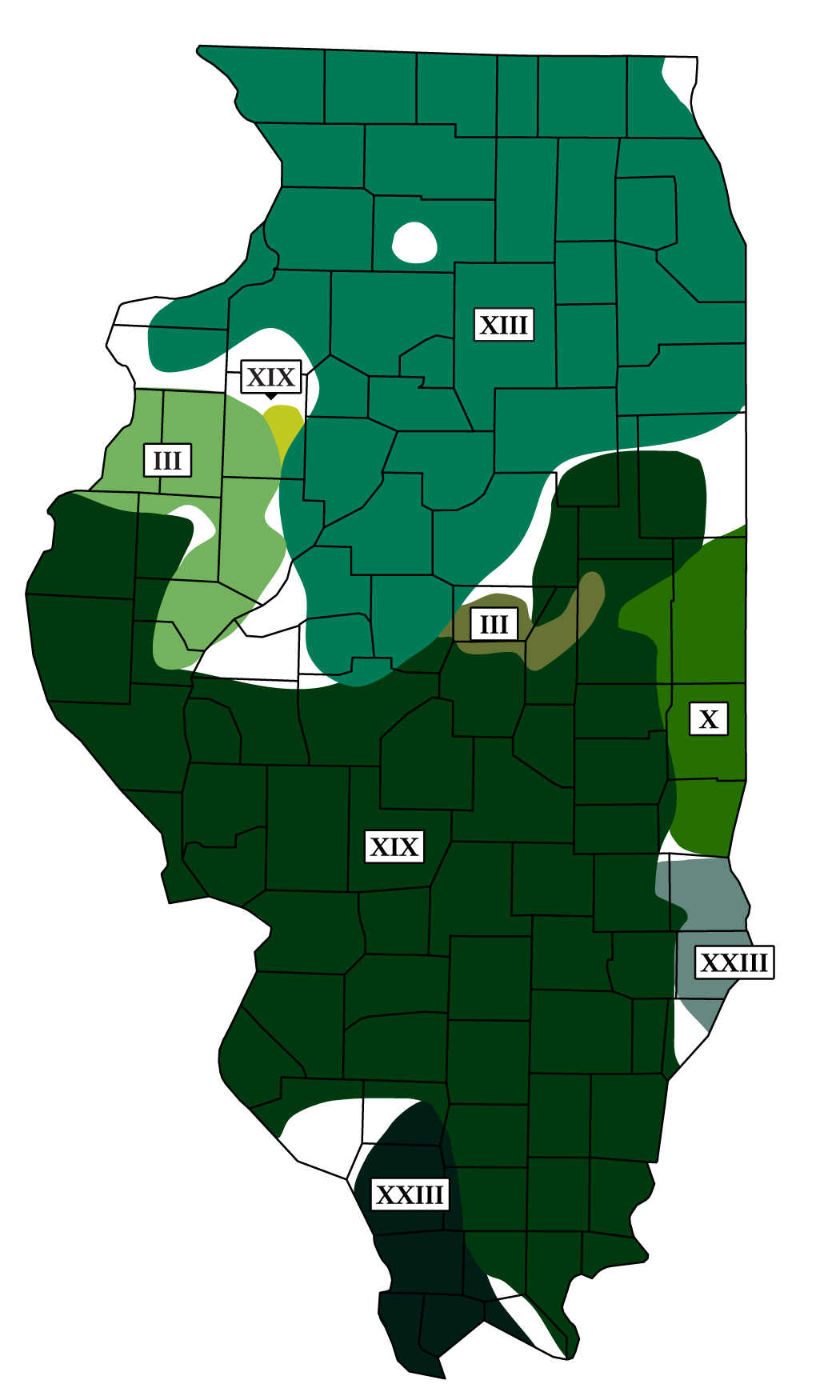

The spring of 2024 will be a banner year for the periodical cicada: Both the 13- and 17-year broods will emerge, bringing cicadas to most of Illinois in May and June. The central portion of the state (Springfield and south), except for a few extreme southern counties, will welcome Brood XIX of 13-year periodical cicadas. Areas north of Springfield, including the Chicago region and far southern Wisconsin, will experience Brood XIII of 17-year cicadas.

Mathematically, it is a very rare event for both 13- and 17- year broods to emerge in the same year (see Figures 1A and B). It happens in Illinois only every 221 years. In fact, the last time these two broods co-emerged was in 1803, the year Thomas Jefferson bought the Louisiana Purchase from France. When I personally experienced the co-emergence in 1998 of the Missouri Broods IV (17-year) and Brood XIX (13-year), it was quite noisy.

Best Management Practices

What can we do to mitigate or prevent ovipositional damage to our younger and more vulnerable woody plants, while at the same time enjoying this unique biological and ecological event? Here are some practical best management practices for homeowners and members of the forestry, orchard, and green industries:

Enjoy the event. This fascinating natural occurrence will only last for a few weeks, and it will be at least 13 years before another periodical cicada emergence.

Consider waiting to plant very young trees. If possible, avoid spring 2024 plantings of very young trees less than 2 inches in diameter/caliper. Consider waiting to plant until after adult cicada activity has ceased, or until fall.

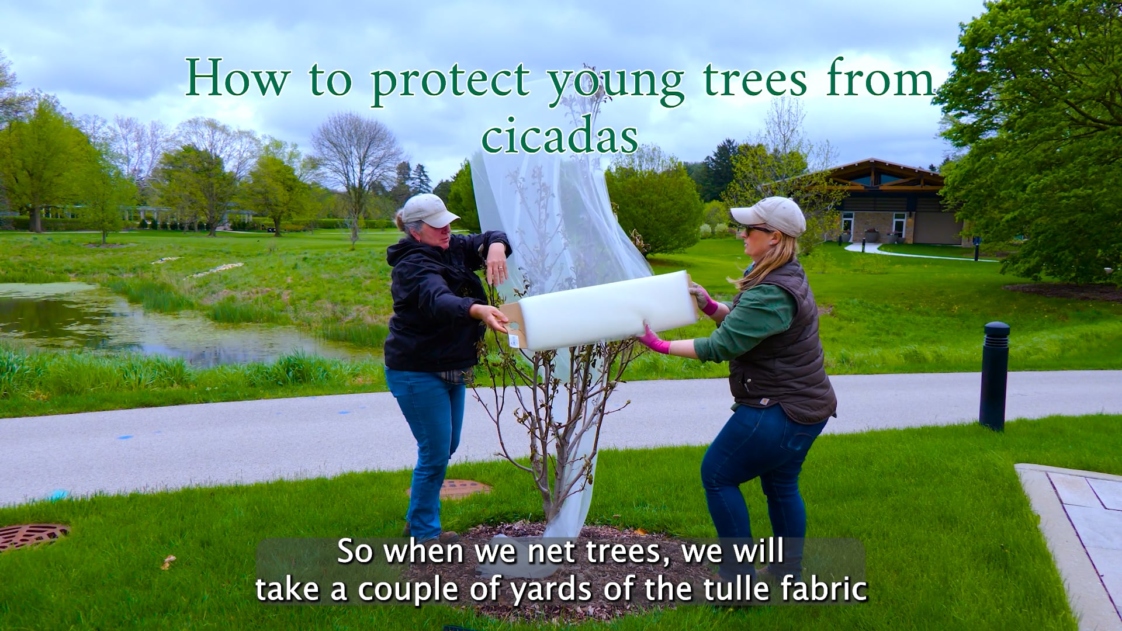

Cover vulnerable small trees with netting. If you have a limited number of susceptible plants, cover them with fine netting (such as the tulle used for ballet tutus). Make sure to gather the netting around the trunk as near to the ground as possible. Once the emergence event is over, be sure to remove the netting.

Avoid contact insecticides. Studies have not shown that application of contact insecticides is effective and it is not practical for large-scale operations. Contact insecticides can be harmful to beneficial insects, leading to insect and mite outbreaks unrelated to the cicada emergence.

Expect natural pruning. Mature and healthy trees will show some terminal branch flagging later in the season, likely in August. This will only result in some “natural pruning” and is not harmful to the plant

Periodical Cicada Life Cycle

There are both annual cicadas and periodical cicadas. Both groups spend most of their life cycle underground. The adult annual cicada emerges from the soil and becomes active every July and August. Periodical cicadas emerge all together in late spring and early summer, generally May and early June. Periodical cicadas are only found east of the Rocky Mountains (Figure 1A). They have 13-year life cycles in the southern states and 17-year cycles farther north (Figures 3 and 4).

The 17-year periodical cicada Brood XIII, which is mostly in Illinois, consists of three species, Magicicada septendecim, M. cassini, and M. septendecula. The 13-year cicada Brood XIX, also known as the Great Southern Brood, is made up of four species, M. tredecim, M. neotredecim, M. tredecassini, and M. tredecula (Figure 1B).

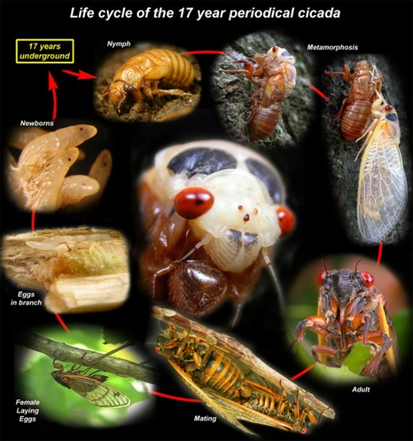

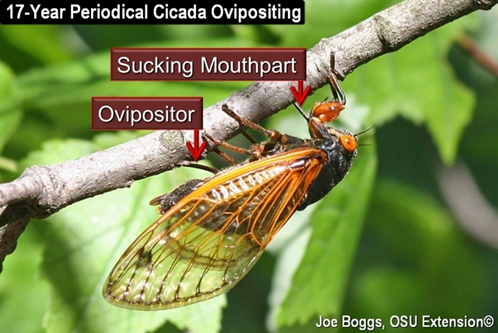

Immature and adult periodical cicadas have piercing-sucking mouthparts that are used for extracting plant sap from fine roots and twigs and branches. The immature nymphs feed on roots underground for 13 to 17 years, depending on the brood. Upon emergence from the soil, adult cicadas briefly feed on a variety of woody plants. Feeding damage from the adults is minimal at most. Most plant damage results from the females using their saw-like ovipositors to lay eggs in small twigs and branches.

Once mating has been completed, the adult females, with their saw-like ovipositors, will begin cutting longitudinal slits in the twigs and branches of woody plants. They will lay up to 20 eggs in each of these “egg nests” (Figures 4, 5, and 6). An adult female can lay up to 600 eggs during her lifetime (Brown and Zuefle, 2009).

After about 6 to 10 weeks, the eggs will hatch into nymphs that will drop to the soil, burrow in, and begin feeding on the fine roots of the host plant for the next 13 or 17 years (Brown and Zuefle, 2009) (Figures 4, 5, and 6).

How Cicadas Affect Trees

While most cicadas are considered generalists, with a broad range of host plants, they have preferences like all living creatures. Preferred plants for egg-laying including apple (Malus spp.), hickory (Carya spp.), maple (Acer spp.), and oaks (Quercus spp.) (Brown and Zuefle, 2009). Members of the birch (Betulaceae), dogwood (Cornaceae), walnut (Juglandaceae), willow (Salicaceae), linden (Tiliaceae), and elm (Ulmaceae) plant families may also be used.

Additional hosts may include introduced exotic ornamentals such as rose (Rosa spp.), cotoneaster (Cotoneaster spp.), forsythia (Forsythia spp.), ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), pear (Pyrus spp.), and lilac (Syringa spp) (Brown and Zuefle, 2009).

Cicadas tend not to prefer plants whose sap or gum may prevent egg hatch or keep nymphs from escaping, such as conifers; sumac (Rhus spp.); cherries, peaches, and plums (Prunus spp.); and persimmon (Diospyros virginiana) (Brown and Zuefle, 2009). For a more comprehensive list of host plants, refer to the following references: Forsythe, 1975; White, 1980; Miller, 1997; Miller and Crowley, 1998; Cook et al., 2001.

While adult ovipositional damage on mature trees and shrubs is usually no more than natural pruning, very young woody plants and whips can be more seriously damaged and even killed. The female cicadas’ ovipositing on the young stems can cause wounds that may lead to breakage of the stem or top kill, and also may provide entry for canker-causing fungi and wood-boring insect pests (Figures 6 and 7). A number of studies have found that there appears to be a minimum and a maximum twig/branch diameter that is preferred for oviposition, ranging from 3 to 11 mm (1/8 to 7/16 inch.) (White, 1980, Karban, 1982, Miller, 1997, Miller and Crowley, 1998).

Ovipositional wounds in mature trees may allow for entry of canker-causing pathogens and wood-boring insect pests. Other forms of cicada damage may come between emergences, when heavy populations of nymphs feed on the fine roots of trees and shrubs. Heavy feeding can cause a reduction in overall plant health and depletion of energy reserves, resulting in decreased flower and fruit production..

Which Trees Are Affected

Host preference of the periodical cicada is not fully understood. Cicadas’ preference for native versus exotic plants, leaf arrangement, resin levels, light, and plant architecture may play a role in determining which plants are utilized for egg-laying. For example, a study in Delaware by Brown and Zuefle (2009) found that nonnative plants tended to be more favored than native plants. In contrast, a study by Miller and Crowley (1998) at The Morton Arboretum found no significant differences in plant damage between natives and nonnatives.

Regarding plant architecture, Brown and Zuefle (2009), in examining 428 plants, found that the probability of oviposition increased with greater branch/twig diameter and also with plant structure. In other words, plants with bushy, dense growth habits or with numerous long branches had higher rates of oviposition but fewer wounds per stem length, compared with plants that had a less dense and a more upright growth habit. Their results suggest that bushy plants or plants with many stems may impede cicada oviposition and also may dilute the number of wounds.

In most situations, conifers are rarely attacked, probably because the arrangement of needles on the twigs impedes the ability of the female to oviposit. The resin also can trap and kill eggs, preventing egg hatch of young nymphs. This also may also be true for gum-producing plants such as Prunus spp. (cherries, peaches, and plums) (White, 1980, Karban, 1983, Cook et al., 2001).

Miller and Crowley (1998) found that conifers and evergreens differed in their susceptibility to ovipositional damage. For example, plants such as hemlock, juniper, arborvitae, and yew with needles or leaf scales that did not completely encircle the twig and twigs that were less stout and flexible did experience some damage, as compared with other conifers that have stouter twigs and needles that completely encircle the branch, such as pines, spruces, and firs. White (1980) found that black walnut (Juglans nigra) and Osage-orange (Maclura pomifera) were rarely used for egg-laying due to their spongy pith, which contributed to egg desiccation.

Stem diameter is also a critical factor. Plants such as tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima), Kentucky coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus), and sumac (Rhus spp.) that had thick, stout stems near or exceeding 10 mm (3/8 inch) in diameter were not attacked. Interestingly, however, female cicadas did attempt to oviposit in the leaf rachis of G. dioicus (diameter 4 mm or 5/32 inch), which is within the range of stem diameters for egg laying.

What about nymphal feeding on plant roots? In a study by Speer et al. (2010), they found no effect from root parasitism (feeding) by cicada nymphs prior to emergence on five Midwestern forest trees: sugar maple (Acer saccharum), white ash (Fraxinus americana),pin oak (Quercus palustris), black oak (Q. velutina), and sassafras (Sassafras albidum). However, three of the species’ chronologies showed a significant reduction in growth the year of or the year after the emergence year, and three chronologies showed an increase in growth five years following the cicada emergence event.

Another interesting phenomenon is that cicadas may use sunlight as a cue in selecting host plants. In field experiments by Yang (2006), it was discovered that female cicadas use the local light environment of host trees during the summer of emergence to select long-term host trees. Light environments may also influence oviposition microsite selection within hosts, suggesting a potential behavioral mechanism for associating solar cues with host trees.

Healing of Egg-Laying Wounds

Once ovipositional damage has occurred, how long is it before the plants “heal up” or callus over the wounds? In two studies by Miller (1997) and Miller and Crowley (1998), examining 140 exotic and native woody plant genera and 14 different urban forest parkway tree taxa, they found that most plants callused over the wounds within one to two years after a cicada emergence. Exceptions were alder (Alnus spp.), black walnut (Juglans sp.), redbud (Cercis sp.), lilac (Syringa spp), linden (Tilia spp.), honey-locust (Gleditsia triacanthos), northern red oak (Q. rubra), hackberry (Celtis occidentalis), Redmond linden (Tilia americana ‘Redmond’), and littleleaf linden (T. cordata), which took at least three years to heal.

Of course, plant health, growing conditions, and level of injury all affect wound healing rates. In spite of heavy ovipositional damage and delayed wound healing on susceptible plants, no significant canker-causing pathogens or insect pest issues were observed on these same woody landscape plants and urban parkway tree taxa.

Use of Insecticides

What about protecting vulnerable plants with insecticides? Miller and Crowley (1998) found that applications of nonsystemic (contact) insecticides were not effective and did not deter adult females from landing on host plants. In a more recent study, Ahern et al. (2005) compared the efficacy of a neonicotinoid systemic insecticide, imidacloprid, and a nonchemical control measure, netting, to reduce cicada injury. They determined that netted trees sustained very little injury, whereas unprotected trees were heavily damaged. Fewer egg nests, scars, and flags were observed on trees treated with imidacloprid compared with unprotected trees. However, the hatching of cicada eggs was unaffected by imidacloprid.

References Cited and Recommended Readings

Ahern, R.G., S.D. Frank, and M.J. Raupp. 2005. Comparison of exclusion and imidacloprid for reduction of oviposition damage to young trees by periodical cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 98(6):2133–2136.

Brown, W. and M.E. Zuefle. 2009. Does the periodical cicada, Magicicada septendecim, prefer to oviposit on native or exotic plant species? Ecological Entomology 34:346–355.

Cook, W.M., R.D. Holt, and J. Yao. 2001. Spatial variability in oviposition damage by periodical cicadas in a fragmented landscape. Oecologia 127:51–61 .

Cook, W.M. and R.D. Holt. 2002. Periodical cicada (Magicicada cassini) ovipositional damage: visually impressive yet dynamically irrelevant. American Midland Naturalist 147:124–224 .

Forsyth, H.Y. 1975.Ovipositional Host Plants of 17-Year Cicadas. Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center Research Circular #210. 20 pp.

Karban, R. 1982. Experimental removal of 17-year cicada nymphs and growth of host apple trees. Journal of the New York Entomological Society 90:74–81 .

Karban, R. 1983. Induced responses of cherry trees to periodical cicada oviposition. Oecologia 59:226–231 .

Miller, F. 1997. Effects and control of periodical cicada, Magicicada septendecim and Magicicada cassini oviposition injury on urban forest trees. Journal of Arboriculture 23(6):225–232.

Miller, F. and W. Crowley. 1998. Effects of periodical cicada (Homoptera: Cicadidae: Magicicada septendecim and Magicicada cassini) ovipositional injury on woody plants. Journal of Arboriculture 24(5):248–253.

Smith, F.F. andR.G. Linderman. 1974. Damage to ornamental trees and shrubs resulting from oviposition by periodical cicadas. Environmental Entomology 3:725–732 .

Speer, J.H., K. Clay, G. Bishop, and M. Creech. 2010. The effect of periodical cicadas on growth of five tree species in Midwestern deciduous forests. The American Midland Naturalist 164(2):173–186

White, J. and C.E. Strehl. 1978. Xylem feeding by periodical cicada nymphs on tree roots. Ecological Entomology 3:323–327.

White, J. 1980. Resource partitioning by ovipositing cicadas. American Naturalist 115:1–28 .

White, J. 1981. Flagging: host defenses versus oviposition strategies in periodical cicadas (Magicicada spp., Cicadidae, Homoptera). Canadian Entomologist 113:727–738.

White, J., M. Lloyd, and R. Karban. 1982. Why don’t periodical cicadas normally live in coniferous forests? Environmental Entomology 11:475–482 .

Yang, L.H. 2006. Periodical cicadas use light for oviposition site selection. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 273:2993–3000.